How to Stop Lying to Ourselves: A Call for Self-Awareness

It was September of 1816 and two Parisian boys were playing in the courtyard of

the Louvre, the famous museum in Paris.

On the other side of the courtyard, a physician named René

Laennec began to quicken his pace as he walked along in the morning sun. There

was a woman with heart disease waiting for him at the hospital and Laennec was

late.

As Laennec crossed the courtyard, he looked toward the two

boys. One of them was tapping the end of a long wooden plank with a pin. On the

other end, his playmate was crouched down with his ear pressed against the edge

of the plank.

Laennec was immediately struck with a thought. “I recalled a

well-known acoustic phenomenon,” he would later write. “If you place your ear

against one end of a wood beam the scratch of a pin at the other end is

distinctly audible. It occurred to me that this physical property might serve a

useful purpose in the case I was dealing with.”

When Laennec arrived at the hospital later that morning, he immediately asked

for a piece of paper. He rolled it up and placed the tube against his patient’s

chest. He was stunned by what he heard next. “I was surprised and elated to be

able to hear the beating of her heart with far greater clearness than I ever

had with direct application of my ear,” he said.

René Laennec had just invented the stethoscope.

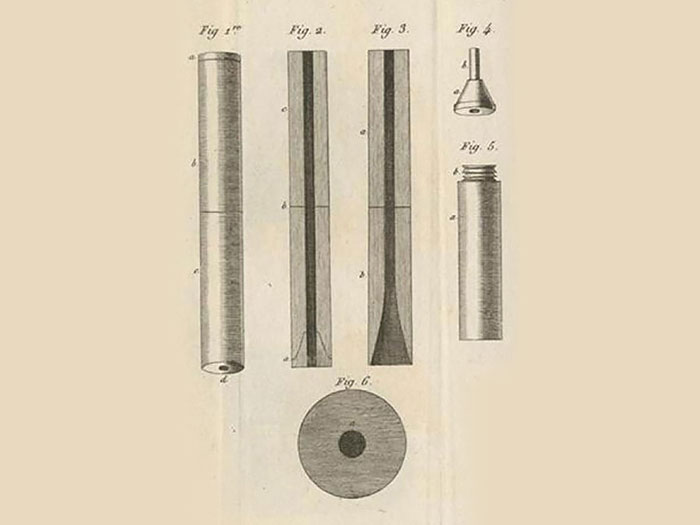

Laennec quickly upgraded from his piece of paper and, after

experimenting with various sizes, he began using a hollow wood tube about 3.5

centimeters in diameter and 25 centimeters long.

This is a sketch of René Laennec’s original stethoscope design, which was

essentially a hollow wood tube. The ear piece is featured in the top right

corner. (Image Source: US National Library of Medicine.)

Laennec’s simple invention instantly changed the field of medicine.

For the first time in history, physicians had a safe,

unbiased way to understand what was going on inside a patient’s body. They didn’t

have to rely solely on what the patient said or how the patient described their

condition. Now, they could track and measure things for themselves. The

stethoscope was like a window that allowed a doctor to view what was actually

happening and then compare their findings to the symptoms, outcomes, and

autopsies of patients.

And that brings us to the main point of this story.

The Lies We Tell Ourselves

We often lie to ourselves about the progress we are making

on important goals.

For example:

If we want to lose weight, we might claim that we’re eating

healthy, but in reality our eating habits haven’t changed very much.

If we want to be more creative, we might say that we’re

trying to write more, but in reality we aren’t holding ourselves to a rigid

publishing schedule.

If we want to learn a new language, we might say that we

have been consistent with our practice even though we skipped last night to

watch television.

We use luke-warm phrases like, “I doing well with the time I

have available.” Or, “I’ve been trying really hard recently.” Rarely do these

statements include any type of hard measurement. They are usually just soft

excuses that make us feel better about having a goal that we haven’t made much

real progress toward. (I know because I’ve been guilty of saying many of these

things myself.)

Why do these little lies matter?

Because they are preventing us from being self-aware.

Emotions and feelings are important and they have a place, but when we use

feel-good statements to track our progress in life, we end up lying to

ourselves about what we’re actually doing.

When the stethoscope came along it provided a tool for

physicians to get an independent diagnosis of what was going on inside the

patient. We can also use tools to get a independent diagnosis of what is going

on inside our own lives.

Tools for Improving Self-Awareness

If you’re serious about getting better at something, then

one of the first steps is to know—in black-and-white terms—where you stand. You

need self-awareness before you can achieve self-improvement.

Here are some tools I use to make myself more self-aware:

Workout

Journal – For the past 5 years or so, I have used my workout journal

to record each workout I do. While it can be interesting to leaf back through

old workouts and see the progress I’ve made, I have found this method to be

most useful on a weekly basis. When I go to the gym next week, I will look at

the weights I lifted the week before and try to make a small increase. It’s so

simple, but the workout journal helps me avoid wasting time in the gym,

wandering around, and just “doing some stuff.” With this basic tracking, I can

make focused improvements each week.

My Annual

Reviews and Integrity

Reports – At the end of each year, I conduct my Annual Review where I

summarize the progress I’ve made in business, health, travel, and other areas.

I also take time each spring to do an Integrity Report where I challenge myself

to provide proof of how I am living by my core values. These two practices give

me a chance to track and measure the “softer” areas of my life. It can be

difficult to know for certain if you’re doing a better job of living by your

values, but these reports at least force me to track these issues on a

consistent basis.

RescueTime –

I use RescueTime to track how I spend my working hours each week. For a long

time, I just assumed that I was fairly productive. When I actually tracked my

output, however, I’ve uncovered some interesting insights. For example, I

currently spend about 60 percent of my time each week on productive tasks. This

past month, I spent 9 percent of my working time on social media sites. If you

would have asked me to estimate those two numbers before using RescueTime, I’m

certain I would have been way off. Now, I actually have a clear idea of how I

spend my time and because I know where I truly stand, I can start to make

calculated and measured improvements.

A Call for Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is one of the fundamental pieces of behavior

change and one of the pillars of personal

science.

If you aren’t aware of what you’re actually doing, then it

is very hard to change your life with any degree of consistency. Trying to

build better habits without self-awareness is like firing arrows into the

night. You can’t expect to hit the bullseye if you’re not sure where the target

is located.

Furthermore, I have discovered very few people who naturally

do the right thing without ever measuring their behavior. For example, I know a

handful of people who maintain six-pack abs without worrying too much about

what they eat. However, every single one of them weighed and measured their

food at some point. After months of counting calories and measuring their

meals, they developed the ability judge their meals appropriately.

In other words, measurement brought their levels of

self-awareness in line with reality. You can wing it after you

measure it. Once you’re aware of what’s actually going on, you can make

accurate decisions based on “gut-feel” because your gut is based on something

accurate.

Footnotes

1. Rubber tubing wasn’t

developed until the second-half of the 19th century, which is when stethoscopes

resembling modern designs were first produced. Further details are explained in

this piece called, “The

Man Behind the Stethoscope” from a 2006 edition of Clinical Medicine

and Research. That article is also the source where I found the quotes from

Laennec used in this article.

2. Thanks to NPR’s Science

Friday segment, where I originally heard the story of the stethoscope from

Ira Flatow and Howard Markel.

James Clear is a writer and researcher on behavioral

psychology, habit formation, and performance improvement. His work is read by

over 500,000 people each month and he is frequently a keynote

speaker at top-tier organizations like Stanford University and Google.

He believes in developing a diversity of knowledge and maintains a public

reading list of the

best books to read across a wide range of disciplines.